PTHG-21: The Fifth Workshop on Progress Towards the Holy Grail

October 25th, 2021, at CP2021

This Workshop is one of a series.

Note: CP2021 and its workshops are virtual, with free registration.

Description:

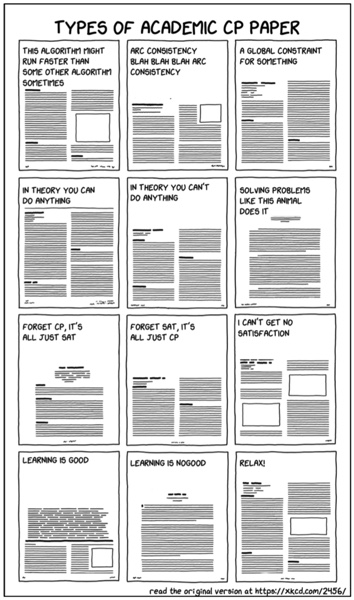

In 1996 the paper “In Pursuit of the Holy Grail” (also here) proposed that Constraint Programming was well-positioned to pursue the Holy Grail of computer science: the user simply states the problem and the computer solves it. It was followed about a decade later by “Holy Grail Redux“, and then about a decade after that by “Progress Towards the Holy Grail“. This series of workshops aims to encourage and disseminate progress towards that goal, in particular regarding work on automating:

- Acquisition: user-interaction, learning, debugging, maintaining, etc.

- Reformulation: transformation for efficient solution, redundant models, etc.

- Solving: adaptive parameter tuning, automated selection from portfolios, learning heuristics, deep learning, etc.

- Explanation: reasons for failure, implications for choices, etc.

Of particular interest is the intersection of the Holy Grail goal with the increasing attention being paid to machine learning, explainable AI, and human-centric AI.

Organizing Committee:

Chair: Eugene Freuder, University College Cork, Ireland, eugene.freuder@insight-centre.org

Christian Bessiere, University of Montpellier, France

Tias Guns, KU Leuven, Belgium

Lars Kotthoff, University of Wyoming, USA

Ian Miguel, University of St Andrews, Scotland

Michela Milano, University of Bologna, Italy

Helmut Simonis, University College Cork, Ireland

Submissions:

Submissions may be of any length, and in any format. They may be abstracts, position papers, technical papers, or demos. They may review your own previous work or survey a topic area. They may present new research or suggest directions for further progress. They may propose research roadmaps, demonstration domains, or collaborative projects. They may be proposals for measuring progress, and, in particular, for data sets or competitions to stimulate and compare progress.

Previously Published Track. Authors are encouraged to submit to this track pointers to relevant papers that they have published elsewhere since the date of the last workshop, PTHG-20, September 7, 2020. The objective is to further the Workshop goal of disseminating progress in this area.

Submissions should be emailed, in PDF form, with subject line “PTHG-21 Submission”, directly to the Workshop chair, at: eugene.freuder@insight-centre.org.

Submissions to the Previously Published Track should be in the form of a PDF that clearly identifies it as a submission to the Previously Published Track, contains bibliographic information on the previous publication, and provides a URL pointing to the paper (if possible without violating copyright, to a full version of the paper).

Authors may make multiple submissions if they wish. All submissions that appropriately address the topic of the workshop will be accepted as is, without further revision, and will be made available at the workshop website.

The deadline for submissions is September 15, 2021. Decisions on acceptance will be sent by September 20, 2021.

Authors of accepted submissions will be expected to upload a video presentation of the requested length by September 30, 2021; otherwise the submission will be withdrawn from the program and proceedings (if any). The conference will host these videos. Details of the upload process will become available.

Website: PTHG-21: The Fifth Workshop on Progress Towards the Holy Grail