The great physicist George Gamow wrote a book entitled One Two Three . . . Infinity: Facts and Speculations of Science, which I recall as one of the books I encountered in my high school library that inspired my interest in mathematics. This post is what I hope will become one of a series on “Where do ideas come from?”. (As always further contributions from readers in the Comments are encouraged.)

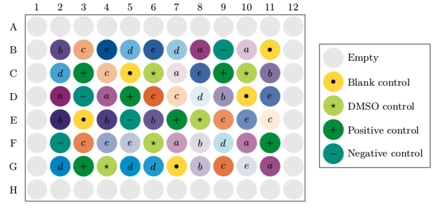

“Consistency”, as a form of inference, is arguably what distinguishes the AI approach to constraint satisfaction. “In the beginning” there were three forms of consistency, which were described in terms of the “constraint graph” representation of constraint satisfaction problems: “node consistency”, “arc consistency” and “path consistency”, which involved respectively nodes (vertices), arcs (edges) and paths (sequences of edges leading from one vertex to another). Nodes, arcs, paths: that seemed to cover the possibilities for graph consistency.

However, Montanari demonstrated that path consistency could be reduced to consistency for paths of length 2, involving just 2 edges. Looking at it in terms of the number of vertices involved: node consistency involves just 1, arc consistency 2, path consistency 3. “Node, arc, path” … it isn’t obvious that there is anything more to see here. But “1, 2, 3” … that practically begs to ask the question: Does it stop there; shouldn’t there be a “4-consistency, a 5-consistency, … ? And thus the idea for “k-consistency” was born. Putting this together with an algorithm for achieving k-consistency (and thus ultimately a complete set of solutions, purely by inference) resulted in an MIT AI Memo in 1976, which in 1978 became my first major journal publication.

There are two meta lessons here with regard to the question “where do ideas come from”.

The first is the importance of representation. A classic example is Kaplan and Simon’s investigation of the mutilated chessboard problem. Here, it was the switch from talking about different graph structures — nodes, arcs, and paths — to talking about the number of vertices involved. Another representational shift — from viewing constraints as represented by edges to viewing them as represented by nodes (in an “augmented” constraint graph) — enabled the algorithm I devised to achieve higher order consistency.

The second is the notion of extrapolation, as an instance of the even broader concepts of generalization and completion. Here “1, 2, 3” suggests “k”. It just doesn’t seem right that we would have to stop at 3. 🙂

Of course, we don’t actually go to infinity — unless we consider problems with an infinite number of variables. Hmm, that’s an idea …